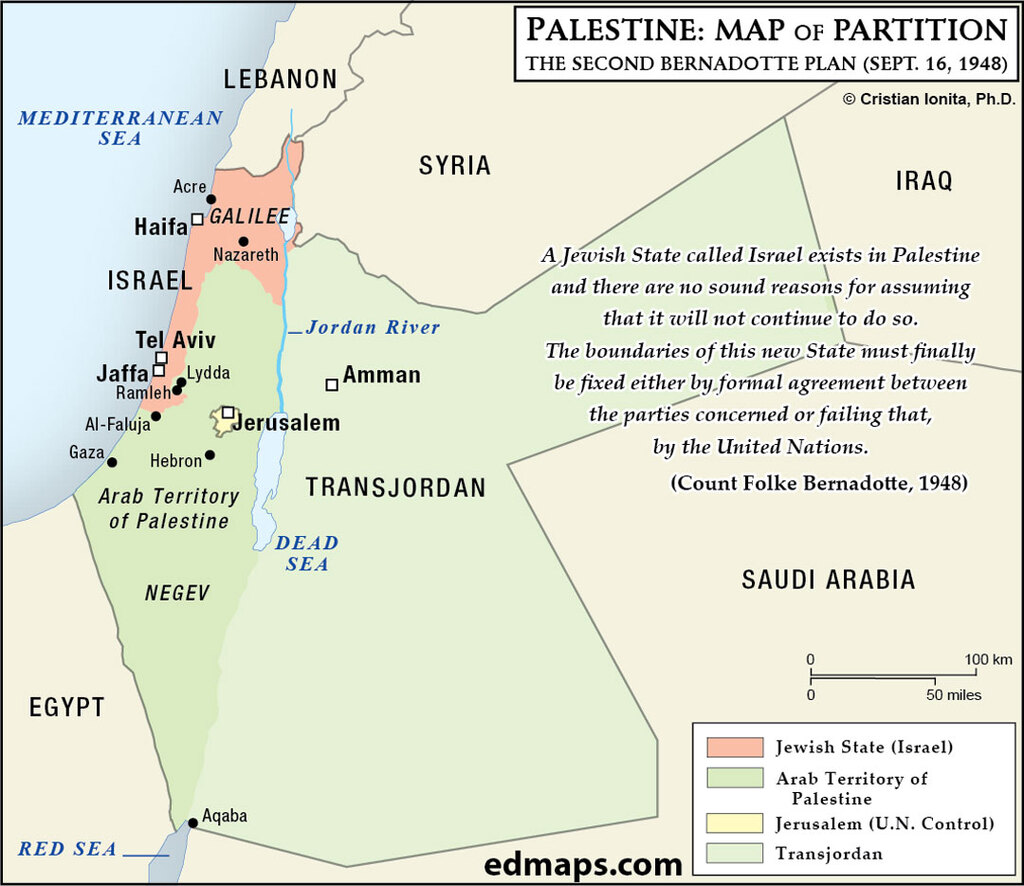

The Second Bernadotte Plan, presented on September 16, 1948, revised the initial proposal to address the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict. Its territorial articles proposed a Jewish state encompassing all of Galilee, the coastal plain, and a portion of the Negev, with defined boundaries. The Arab state, to be united with Transjordan, would include Judea, Samaria, the Jordan Valley, and most of the Negev, including Beersheba. Jerusalem would remain under international administration. The plan aimed for an economic union and peaceful coexistence but was rejected by both Arabs, opposing any Jewish state, and Jews, seeking more territory.

By September 1948, the Arab-Israeli war had fundamentally altered the strategic landscape of Palestine, making Count Folke Bernadotte's initial June proposal obsolete. Military victories had shifted territorial control, refugee flows had created new humanitarian crises, and the political dynamics had evolved significantly since his first mediation attempt. Against this backdrop, Bernadotte presented his Second Plan on September 16, 1948, representing what would tragically become his final effort to broker a comprehensive peace settlement before his assassination just one day later.

The Second Bernadotte Plan demonstrated the UN mediator's ability to adapt his proposals to changing military and political realities. Unlike his June proposal, this revised plan acknowledged Israeli military successes by awarding the Jewish state significantly more territory, including all of Galilee—a region of strategic and agricultural importance that had witnessed fierce fighting. The Jewish state would also retain the entire coastal plain, providing crucial access to Mediterranean ports and the economic infrastructure that had developed under the British Mandate. Additionally, Bernadotte conceded a portion of the Negev Desert to Jewish control, recognizing both military facts on the ground and the potential for future development in this sparsely populated region.

However, the proposed Arab state would still encompass substantial territories, including the central highlands of Judea and Samaria, the fertile Jordan Valley, and most of the Negev Desert, including the important town of Beersheba. Crucially, this Arab state would be united with Transjordan under King Abdullah's rule, reflecting both Abdullah's territorial ambitions and Bernadotte's pragmatic assessment that Jordan possessed the administrative capacity and political legitimacy necessary to govern these areas effectively.

Jerusalem's status remained unchanged from the first plan, with the city designated for international administration—a provision that continued to reflect international consensus about the city's unique religious and political significance. The plan maintained its emphasis on economic union between the two states, recognizing that geographical proximity and shared infrastructure made continued cooperation essential for both entities' prosperity.

Despite these territorial adjustments, which ostensibly offered something to both sides, the Second Bernadotte Plan met the same fate as its predecessor. Arab leaders maintained their fundamental rejection of any arrangement that legitimized Jewish sovereignty in Palestine, regardless of territorial configurations or boundary adjustments. The Jewish leadership, emboldened by military successes and facing pressure from maximalist factions, sought even greater territorial gains and refused to accept limitations on their expansion, particularly in Jerusalem and the Negev.

The plan's rejection underscored the tragic reality that by September 1948, positions had hardened to the point where even a more generous territorial arrangement could not bridge the fundamental gap between competing national narratives and territorial aspirations.