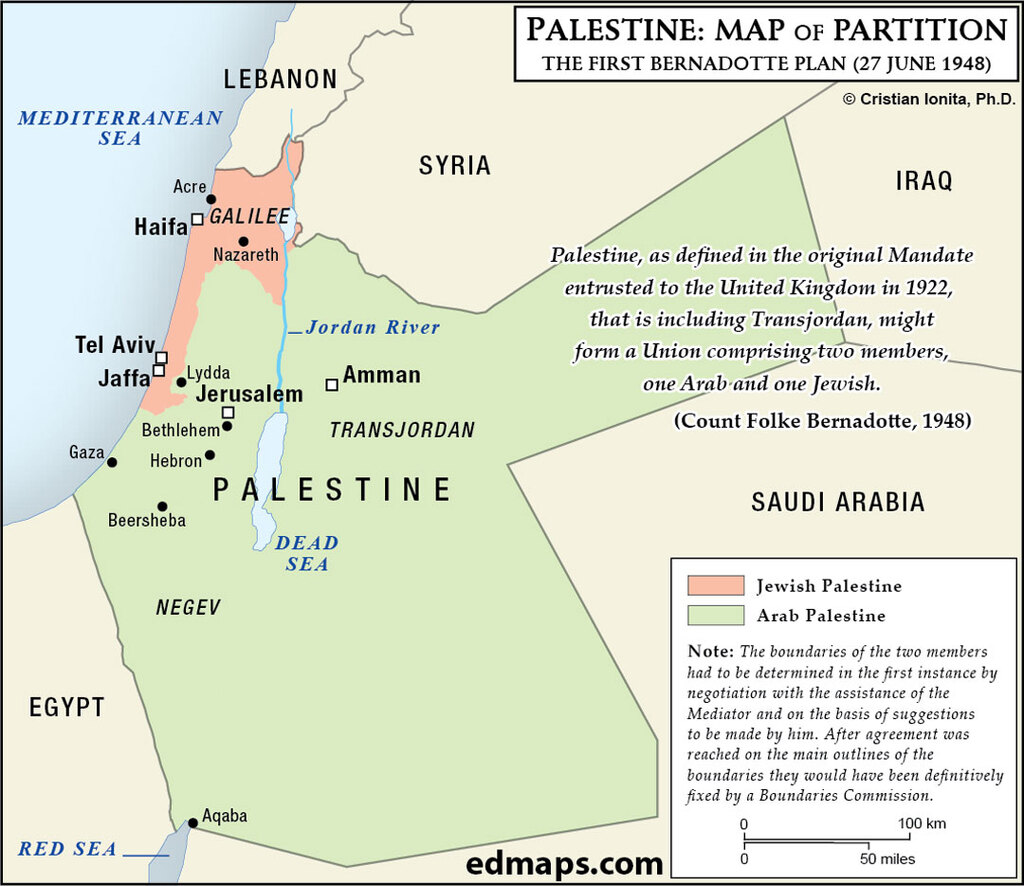

The First Bernadotte Plan, proposed by UN mediator Folke Bernadotte on June 28, 1948, aimed to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict after the 1947 UN Partition Plan’s failure. Its territorial articles suggested a union of two states — Jewish and Arab — with defined boundaries. The Jewish state would include the coastal plain, the whole or part of Western Galilee, and the Jezreel Valley. The Arab state would encompass Samaria, Judea, and the Negev, with Transjordan annexing most Arab areas. Jerusalem would be under international control. The plan emphasized economic union and cooperation but was rejected by both sides, with Arabs opposing any Jewish state and Jews resisting territorial concessions.

The collapse of the 1947 UN Partition Plan and the outbreak of full-scale war between Arab states and the newly declared State of Israel created an urgent need for international mediation. Into this chaos stepped Count Folke Bernadotte, the Swedish diplomat appointed as UN mediator, who on June 28, 1948, presented his First Bernadotte Plan — a comprehensive territorial solution that would fundamentally reshape the political landscape of Palestine. His proposal emerged during a critical moment when the first Arab-Israeli war had already demonstrated the inadequacy of the original partition boundaries and the need for more pragmatic territorial arrangements.

Bernadotte's plan represented a significant departure from the 1947 UN Partition Plan, reflecting the military and political realities that had emerged during the ongoing conflict. Rather than maintaining the complex patchwork of territories envisioned in the original partition, the First Bernadotte Plan proposed a more coherent territorial division that would create two geographically unified states. The Jewish state would encompass the coastal plain, western Galilee, and the strategic Jezreel Valley, areas that formed a contiguous territory along the Mediterranean coast and provided natural defensive boundaries. This configuration would have given the Jewish state control over the most economically developed and agriculturally productive regions of Palestine.

The proposed Arab state would control the central highlands of Samaria and Judea, along with the vast Negev Desert in the south. Crucially, Bernadotte's plan envisioned that Transjordan would annex most of these Arab areas, effectively incorporating them into King Abdullah's expanding kingdom. This arrangement reflected both Abdullah's territorial ambitions and the mediator's assessment that Jordan possessed the administrative capacity and political stability necessary to govern these territories effectively.

Perhaps most controversially, Jerusalem would remain under international control, continuing the internationalization concept from the original UN plan but in a dramatically altered context. The plan also emphasized the importance of economic union and cooperation between the two states, recognizing that geographical proximity and shared infrastructure necessitated continued collaboration despite political division.

However, the First Bernadotte Plan faced immediate and vehement opposition from both sides. Arab leaders rejected the proposal entirely, maintaining their fundamental opposition to any Jewish state regardless of its boundaries or configuration. For them, any recognition of Jewish sovereignty in Palestine remained unacceptable. The Jewish leadership, while more receptive to negotiation, resisted the territorial concessions demanded by the plan, particularly the loss of Jerusalem and significant portions of the territory they had hoped to control.

The plan's failure highlighted the deep-seated maximalist positions that would continue to plague Arab-Israeli relations for decades. Bernadotte's pragmatic approach, which sought to balance competing national aspirations with geographical and economic realities, ultimately proved incompatible with the uncompromising positions of both parties in this intensely emotional and ideological conflict.